Red Sneakers for Oakley~

“How much do you really know?”

I am not a “peanut-allergy-mom” says Tatiana Platt and until recently she didn’t even know that such a term existed. Unlike the many parents who help their children navigate the world of living with a food allergy, Tatiana does not have children with food allergies. Yet 1 in 13 children in the U.S. have a food allergy. 15 million people have a food allergy in the U.S. alone.

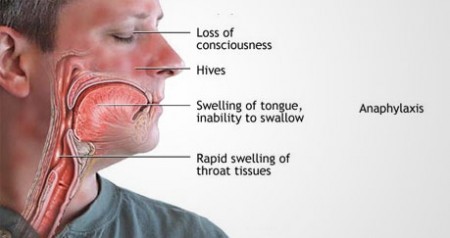

This staggering fact was evidenced to Tatiana in a very tragic way late last year. She received a text telling her that the son of a friend was in critical condition in the hospital. She didn’t know why, but promised to say a prayer and hoped for the best. A day later, she got the news. 11 year old Oakley had died in the hospital. The cause: Anaphylaxis. A severe reaction caused by accidental exposure to nuts, to which Oakley was allergic. How could this be? What? Death? What happened?

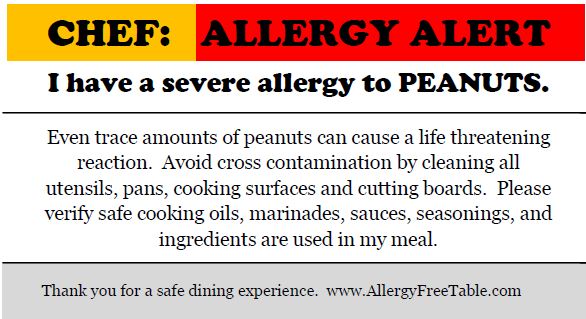

As she describes it, Tatiana would soon come to find out that severe reactions to food allergies are some parents’ biggest nightmare. With children going to school every day, being invited to playdates, eating out in restaurants, living a “normal” life, accidental exposure to an allergen can happen all too easily. And that doesn’t include the dangers posed by troublesome food allergy bullying that takes place even in schools with well-intentioned policies and practices. The parents, the children, their teachers, their family, might be prepared with their “Allergy Emergency Action Plan” and be sure to always have an epipen in the event of a severe reaction. But what happens when you aren’t sure whether your child is having a severe allergic reaction?

Oakley was visiting family in Maine and was having a great time playing with his cousins and his twin sister, Olivia. On his way through the kitchen, he saw a pound cake on the counter and grabbed a piece. He ate it. But it tasted funny. It tasted like nuts. Oakley went to tell his mom. She tasted it. Yes, it sure did taste like nuts, but there was no label of ingredients. Oakley started to get a blister on his lips. So his mom gave him Benadryl. That always worked. And it did the trick this time too. Oakley ran off to happily play with his cousins again.

Problem was, deep down in Oakley’s body, an anaphylactic reaction had begun, but there were no immediate outward signs. It wasn’t until an hour later when Oakley felt nauseous and vomited that he showed a sign of anything else. And then he experienced difficulty breathing. By the time Oakley’s family realized something was very wrong and gave him the epipen, it was too late.

Oakley’s family, friends and everyone in the community where he lived entered a state of shock from the tragedy. Oakley’s mom and dad felt betrayed by their doctors for not having been better informed about their son’s allergy. They were devastated that they had not known to give the epipen when it was sitting there in the house the whole time. They bemoaned the likelihood that another parent might have to be in their shoes. They had to do something.

Red sneakers were Oakley’s favorite shoes. In the days following Oakley’s death, somewhere deep inside, Oakley’s mom and dad found the strength to create an idea – let’s start a movement for food allergy awareness and call it “Red Sneakers for Oakley”. Oakley’s aunt set up a Facebook page and people started posting photos of red sneakers.

That’s when Tatiana took over. She told Merrill and Bobby, “let me handle this”, and took on the effort to coordinate the social media and PR outreach for Red Sneakers for Oakley. They knew what they were doing was important, but neither she nor the Debbs had a real sense of how huge the movement they were creating was going to become.

Red Sneakers for Oakley’s presence on social media platforms has gone on to galvanize an online movement that did not exist before. The dangers of food allergies are known to the parents of children who have them, but many people overlook the severity of accidentally ingesting an allergen. The red sneaker symbol has become a unique identifier in today’s social media environment, and is resonating with millennials and Gen X’ers alike. To date, they have received thousands of messages and posts from people all over the world. Their Facebook page has attained close to 8,000 followers in a little over 3 months. They are also active on Instagram, Twitter and Pinterest, with a growing audience of a combined 100,000+.

Due to the powerful message of Red Sneakers for Oakley, they receive almost daily testimonials of parents who might otherwise have suffered a tragic incident with their own children had they not been made aware of Oakley’s experience. They are dedicated to making sure that no other parent, family or community has to suffer the same loss and is empowered to take the necessary steps to recognize and treat a severe reaction to a food allergy.

But they still have a long road ahead of them to get their message out to the millions of people who know someone with a food allergy. To that end, Tatiana came up with the idea to launch a “20 for Oakley” fundraising campaign in honor of Oakley. The 20 for Oakley campaign calls on supporters to make a donation of $20 in tribute to Oakley’s soccer jersey number, and to enlist others to do the same by submitting photos online on social media.

Tatiana is donating her time and efforts to Red Sneakers for Oakley because she knows they can make a difference. It tugs at her heart every time she thinks of the pain that the Debbs are going through. Yet somehow they are managing to be strong and focus on turning Oakley’s death into a message that prevents further deaths. And to change people’s perspective on food allergies. The next time an airline attendant announces that peanuts will not be served during a flight’s beverage service because there is someone on board who has nut allergies, take a minute to wonder what else you can do to be mindful of a person with food allergies.

———————————

To participate in the 20 for Oakley campaign, you can support Red Sneakers for Oakley by posting online a photo of red sneakers, ideally with a $20 bill. Here is a suggested caption:

I am proud to support the #20forOakley campaign to raise awareness for food allergies. I am donating $20 to @redsneakersforoakley to continue to spread the message about the dangers of food allergies and anaphylaxis. Please join me in supporting #redsneakersforoakley {@friend1} {@friend2}. Let’s make a difference for the millions of people living with food allergies. #livlikeoaks Donate at REDSNEAKERS.ORG

(1) follow @redsneakersforoakley

(2) use the hashtags #20foroakley #redsneakersforoakley #livlikeoaks

(3) tag 2 friends in your post and ask them to support the campaign

(4) make a $20 donation online at REDSNEAKERS.ORG.

For more information or if you have any questions, feel free to email redsneakersforoakley@gmail.com.

Written By: Tatiana Platt